Abstract

Despite the hardships that accompanied the Covid-19 pandemic, the video game industry continues to thrive and the effects of its addictive qualities are being felt more prominently. The need for a solution against the gaming disorder becomes more dire as the pandemic contributes to an increase in video game engagements. There have been several attempts in the past at combating growing addiction, such as the “Shutdown System”, “Selective shutdown policy” and the “Fatigue system”. All policies and legislations have been and are attempts at controlling the amount of video game exposure their minors experience. During my research, I’ve come across many online forums, led by advocates, that address gaming addiction as well as provide resources to help treat said issue. Some examples include Game Quitters, StopGaming, On-Line Gamers Anonymous, and VideoGameAddiction.org. Currently, advocates for gaming disorder face the obstacle of an unaware audience. Despite there being many platforms that provide information and resources, the issue of gaming addiction isn’t well known enough for these forums to be fully utilized. Legislations that were mandated in China and South Korea haven’t had lasting effects because “the policies outlined only address or influence specific aspects of the problem” (Király et al.). There are a lot of elements that need to be addressed in order for there to be active change in this issue. Advocates right now would need more power and support from others. I believe that these online forums have the potential to be effective and may even be a solution for increasing awareness, but they lack the voice that legislations have. China and Korea have not only grasped the attention of their people through these policies, but the attention of those in other countries. Even though previous policies had their flaws, it brought awareness to the issue and showed that this problem is becoming eminent enough to require concern. One solution cannot solve everything, so policymakers would have to work hand in hand with others, such as “family members, treatment providers, prevention experts, game developer companies” as well as gamers themselves, in order to spread awareness and create a powerful solution towards preventing and treating gaming addiction.

Video Game Addiction : Normalize, Make Aware, and Personally Treat Gaming Disorder

During the Covid-19 pandemic, the video game industry reaped unintentional benefits as all were forced into an unprecedented lockdown. With extra time on their hands, people started finding ways to entertain themselves and satisfy their growing need to indulge in social play. Seeing as how video games provide a lot of what people craved during their time in quarantine, the booming increase in game play was both surprising and yet justifiable. The issue we start to face with this, is the fact that, though they are not always a result of one another, significant game play is correlated with gaming addiction, a problem that is steadily rising. It is a severely underrated issue in relation to how many people are affected and are at risk for it. Advocacy for this concern starts with increasing awareness, normalizing its presence in mainstream media, and using treatment plans that approach those who are affected personally, not through video games themselves. Unlike previous attempts at treating gaming addiction, this method would pry open the problem from its roots instead of merely grazing its surface. To create lasting change, advocates should not be finding ways to limit gameplay, but instead reasoning why gamers find solace in video games in the first place and how to help them find other ways to deal.

Fig. 1. Game drop after China's restrictions on game play

The video game industry has made such an impact globally, that gaming addiction has become a universal problem. Unlike how easily this issue affects gamers worldwide, a common solution has yet to be, and may never be, found. Throughout the years, there have been several attempts at combating growing addiction by both China and South Korea, such as the “Shutdown System” as well as the “Selective shutdown policy” and “Fatigue System” in Korea and China respectively. These have been and are attempts at limiting, blocking, preventing, and overall controlling the amount of video game exposure their minors experience. These policies have not been considered here because “in Asian countries where government control is strong, many of these actions could be implemented,” however, “in the Western world, most of these policy actions would perhaps be highly criticized and protested against as being an attack on civil liberty” (Király et al.). In contrast to China and South Korea’s belief that “problematic Internet use and video gaming are considered serious public health issues…the Western World [is] mainly limited to the rating system evaluating content and age-appropriateness rather than overuse.” This means that while Asian countries trust in policies, that will manage the amount of screen time available to their gamers, countries like America are satisfied and more concerned with providing warnings about the game and leaving the choice up to their consumers. With differing political systems, it is “important to note that general cultural factors and changes need to be taken into consideration when planning policy actions.” This fact is easily reflected through the efforts made by various countries to combat the issue of gaming addiction the way they see fit. The dilemma here is that policy actions, despite reflecting cultural factors, are not aiming at the root of the problem. These policies, including China’s recent implementation of a “nationwide electronic ID authentication for minor gamers” (Global Times), have been proven to be weak and unfavorable mandates, yet policymakers continue to lay out similar orders. “The reason for this may lie in the fact that the policies outlined only address or influence specific aspects of the problem” (Király et al.). The adverse effects that prolonged gaming addiction has on people’s personal lives have convinced advocates that “early intervention is critical in order to minimize harm to the affected individual” (Video Game Addiction). It is likely that this mindset has influenced countries, like China and Korea, to set boundaries and limits on their minors early on in hopes of “contributing to a positive outcome” (Király et al.). Essentially, the goal here is to restrain the younger audience, who are heavily targeted by games due to their susceptibility, to avoid their chances of becoming addicted. It may also serve as a tactic to see video games as a privilege and not something you are allowed to regularly revert towards. In contrast to forceful political mandates, other efforts of advocacy include advocates who reachout through forums. All platforms started out differently and at different times, but they all aim to spread awareness and share resources for a matter they were commonly affected by. “In forums like StopGaming, struggling players” (Hsu), seek comfort in others through consulting, or help others by sharing their stories. Instead of being a source for reliable information on the matter, StopGaming, which is provided through Reddit, is mainly used as a way to connect with a community of members who are going through similar stages of gaming addiction. Other advocates, seen on Game Quitters, On-Line Gamers Anonymous and VideoGameAddiction.org, do their best to make others aware of the gaming disorder, how to identify it, and how to seek help. This advocacy effort is more promising because it has the potential to reach addicts all over the globe and spread awareness faster to a wider audience. The community of advocates is still small and they lack the voice needed for this vast issue, however, with support they would be a great asset for gamers to seek help.

Fig. 2. Escaping video game addiction: Cam Adair at TEDxBoulder

Taking into consideration previous oversights, my evaluation of advocacy entails more diverse ways of spreading awareness and treatment of video game addicts like other addiction patients. When suspicions of gaming addiction started to roam, it was “naturally” placed as a side effect of other conditions instead of granting its own interest. This is reason for concern because there is still uncertainty about how to classify and deal with gaming disorder. To be straight, the “fundamental factors which lead to video game addiction are the same factors that typically lead to other pathological dependencies: depression, anxiety, social difficulties, etc” (Baker 52). This means that gaming addiction should be seen as its own issue, but warrant the same kind of attention as other behavioral addictions. The seriousness around gaming disorder still has yet to be established, so gaming addicts need to be reassured that they will be treated and handled as actual patients. People are still so caught up in the gaming portion of gaming disorder that the objective of treatment, which should specifically be to help the person, is often lost. Instead of limiting exposure to video games, like aforementioned policies, we should be focused on helping addicts “understand why [they] play games [and help said patients] move on from them” (TEDx Talks). “Like other addicts, compulsive gamers are often trying to escape problems in their personal lives” (Video Game Addiction). There is a “neurological element to gaming addiction” which means that “when they play, their brains produce dopamine, giving them a high similar to that experienced by gamblers or drug addicts.” China’s mandates, in this case, would be like forcing an addict to quit cold turkey with no other means to cope or recover. Advocating for patients include educating, being present, giving proper care, listening, and offering resources. Whether you know someone personally or are a treatment provider for an addict in recovery, you need to be understanding of their situation and realize that there is something wrong outside of their life playing games. Spreading awareness, in my opinion, does not always have to be public. A personal or private conversation about a certain matter can often be as enlightening as a full blown campaign. Recovery is a gradual process and one that can’t be rushed, which means that no one can do this alone. My powerful solution for this issue requires a group effort, meaning that “gamers, friends and family members, treatment providers, prevention experts, game developer companies, and policymakers” (Király et al.), must be involved in the push for awareness that precedes care. Reach out to those who you think need to be aware of this issue. In addition, I believe that awareness for video game addiction can be shared in a similar manner to that of other addictions. Just like the ads advocating against cigarettes, vapes, drugs, alcohol, or conditions such as depression and anxiety, gaming addiction can and should be talked about and normalized in mainstream media. Gaming disorder deserves to be seen and heard the way other disorders are. Policies may speak louder, but they may not be heard as clearly, or acknowledged as dearly, as common knowledge. My public act of advocacy and awareness, in addition and in contrast to the more personal effort mentioned beforehand, would be to encourage advocates to be seen before being heard. People will not listen to what you are advocating for if they do not even know you, or the cause you are supporting, exists. If getting an ad agency to officially acknowledge gaming addiction is too difficult at this current stage, advocates should pump information through social media, news articles, or Youtube videos. Means of advocacy do not have to be as official as policy actions. It may even play in your favor to use the internet to your advantage.

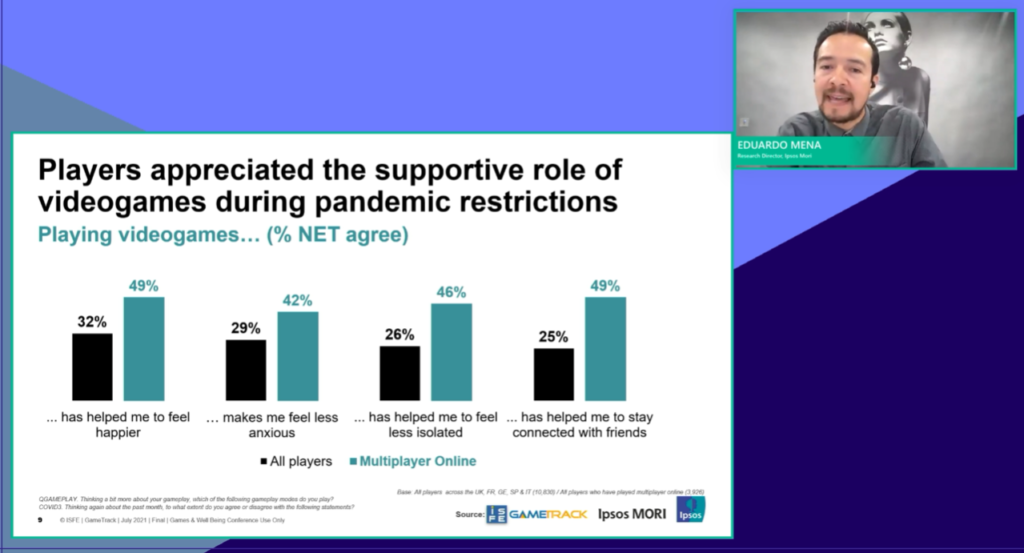

Fig. 3. Video games played a larger role in people’s lives during the Covid-19 pandemic

The major obstacle that stops advocates from successfully reaching out to people has to do with the numerous doubts surrounding the issue of video game addiction. The lockdown that was ensued due to the Covid-19 pandemic forced people to find “alternative methods of communication and engagement” (Santos). Video game consumption and involvement exponentially increased as “people found solace in video games…to share and keep in touch with peers while playing together.” Advocates who support game play have thought this reason enough to argue against gaming addiction. There are those who believe that concern over gaming addiction is over dramatic and that there are plenty of positive benefits that come with indulging in video games. “A study, conducted by the Oxford Internet Institute, examined the top 500 games on Steam, a video game distribution service, and compared daily play data for 2019 and 2020.” Santos, the author of the referenced article, argues that “while the heightened video game engagement led to concerns of possible addiction, the study also found that when lockdowns eased, the engagement also waned again.” This reasoning pushes for the fact that the pandemic does not contribute to gaming addiction because the numbers went down after restrictions started opening up. This claim, however, cannot be supported because this does not change the fact that the number of gamers increased. The hours of screen time increased. This source only proves that the numbers went down from what it was at the peak of the pandemic, not since before the Covid-19 lockdown. The term addiction is brought up, but never properly argued against. Just because “engagement also waned” does not mean gaming addiction is suddenly no longer an issue. Based on another study done by the Oxford Internet Institute, Santos claims that “the experience during play could be more important than the actual amount of time a player invests in games and could play a major role in the well-being of players.” In fairness, video games do provide a sense of entertainment, stress relief, distraction, and connection for those who play. During the pandemic, there was too much out of the ordinary for people to function without a way to interact. (Fig. 4. Video games, such as Sea of Solitude, are finding ways to engage with their consumers through means of reliability.)

Fig. 4 Video games, such as Sea of Solitude, are finding ways to engage with their consumers through means of reliability

In spite of this, I find this opinion to be flawed due to the bias that underlies it. The wording almost implies that video games were the only option for players when it is true that they were capable of occupying themselves through other activities. Saying that video games are the only option to provide social interplay and satiate boredom is even more of a reason to see it as addiction. The video game Sea of Solitude, which allows “players to normalize mental health conversations through an active form of storytelling,” is mentioned as evidence of a video game providing a positive influence over its players. From this point of view, these aspects of video games may seem comforting and appealing, but in reality, it should reflect how the gaming industry takes advantage of people’s need for escape. Games are created with the intent of a trap. Sea of Solitude may seem helpful to those who sympathize with its characters, but it really only provides escapism. To the author’s credit, the article was written in a way that presents their argument in the best ways possible. It shows how games can be beneficial when played a reasonable amount. The complication with this statement, however, has to do with the fact that increased screen time is being normalized. It seems as though logging more screen time is somewhat of an accomplishment now, than a concern. Gaming addiction will continue to prosper and infect players if not properly addressed. It does not matter that video game usage has gone down since the peak of the pandemic because “most players (90%) said they will continue playing” (Snider), even after lockdown procedures loosen up. The overall impact the Covid pandemic has had awakens bigger concerns within advocates. “Given that we now live in an entirely technology-based world, overpathologizing behaviors that were unusual a few decades ago but have become parts of normal life today may be more harmful than beneficial for some individuals” (Király et al.). It makes sense that people are not recognizing the consequences of video games because of what it has come to represent in today’s day and age. Admitting, acknowledging, or diagnosing gaming disorder can seem unreasonable in the society that we now live in. Finding solace in games to occasionally have fun, unwind, or interact is not out of the ordinary. It is when the term solace becomes an excuse for escapism and a means to avoid other tasks required in your life, that it becomes an addiction. This advocacy is necessary because non-believers are only hurting themselves by refusing to believe video game addiction is real.

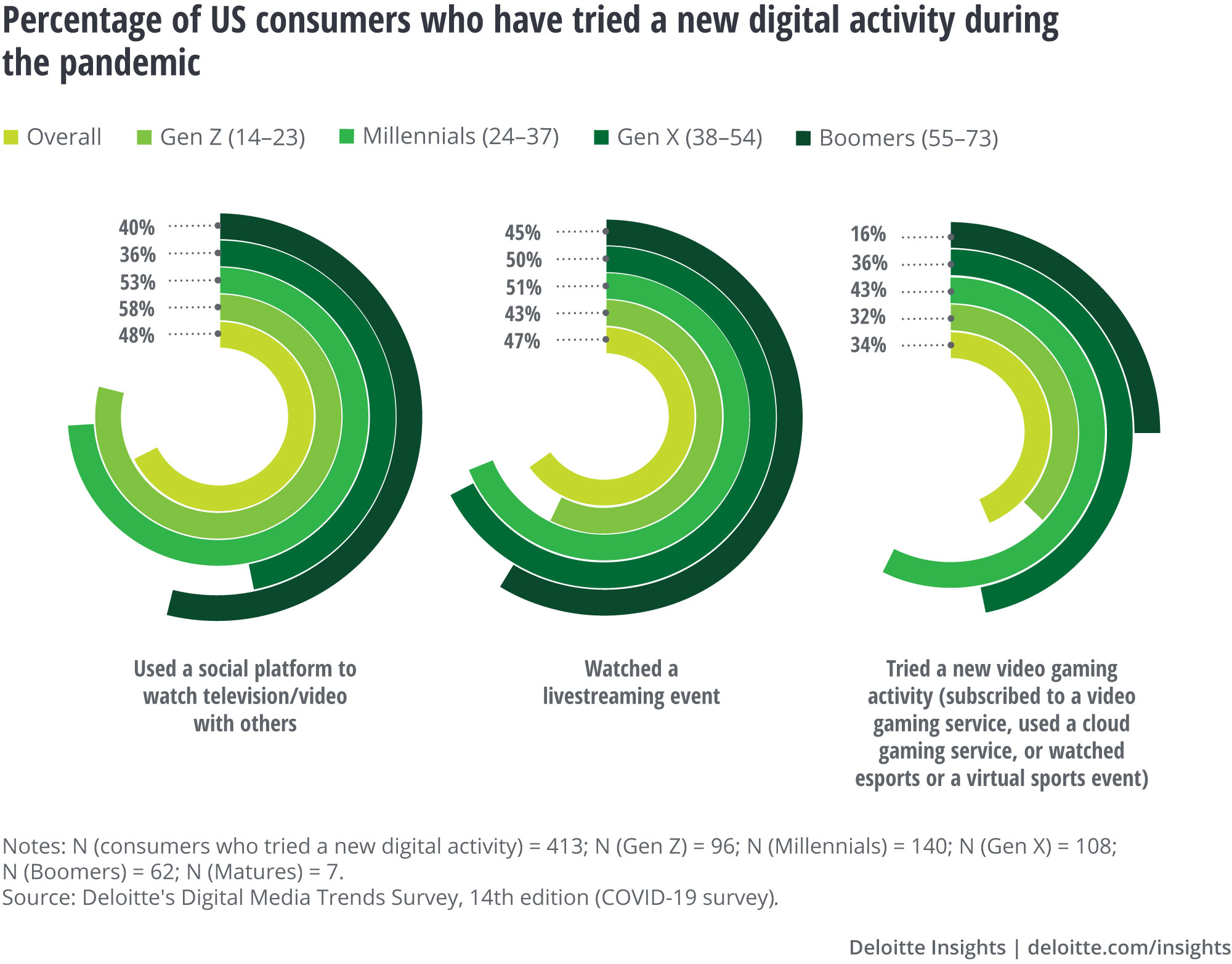

Fig. 5. Percentage of US consumers who have tried a new digital activity during the pandemic

The advancements in the video game industry are surpassing our ability to manage its detrimental effects. Engagement with it, reliance on it, and addiction to it have all increased and will continue to do so. The developments over the Covid pandemic show how easily things can escalate without other means to contain it. This universal issue that I want to advocate for requires awareness more than mandates. The problem is not video games themselves, but how people use it as a coping mechanism to fill holes or replace elements in their lives with it. Policy measures can be implemented, but they will never be effective until people decide for it to be. Lasting changes come after dealing with the source. All efforts to help must keep in mind the standards of the society we now live in and focus on how to treat compulsive gaming before it negatively and permanently affects our circadian rhythm of play.

Works Cited

Baker, Christopher J. “Video Games: Their Effect on Society and How We Must Modernize Our Pedagogy for Students of the Digital Age.” VCU Scholars Compass, 2014, https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4626&context=etd. Accessed 24 February 2022.

Christopher J. Baker published this source as his dissertation on VCU Scholars Compass in 2014. In his thesis, he discusses the effect video games have on society and how its use in today’s digital age has made it controversial when addressing its addictiveness. Video games now “offer players so much more than just an ‘escape’” from society, making it more difficult for people to step away. Positive psychology is mentioned several times to explain why video games draw people in and cause addiction. “The fundamental factors which lead to video game addiction are the same factors that typically lead to other pathological dependencies: depression, anxiety, social difficulties, etc” (52). It is important for my issue that gaming disorder is addressed as seriously as other disorders, but treated in its own unique way.

Billieux, Joёl, et al. “Are we overpathologizing everyday life? A tenable blueprint for behavioral addiction research.” AKJournals, 2015, https://akjournals.com/configurable/content/journals$002f2006$002f4$002f3$002farticle-p119.xml?t:ac=journals%24002f2006%24002f4%24002f3%24002farticle-p119.xml. Accessed 24 February 2022.

This article published on AKJournals, by Joёl Billieux, Adriano Schimmenti, Yasser Khazaal, Pierre Maurage, and Alexandre Heeren, on September 1, 2015, covers a section of behavioral addiction that I had not considered before. I found this source through another article and found it to be useful in understanding why it’s difficult to limit game play in today’s society. The article claims that “everyday life behaviors tend to be too easily overpathologized and considered as behavioral addictions” (22). This gave me a new perspective into why some may believe video game addiction is not an addiction, but a reflection of game play in today’s society.

Dorgruel, Leyla, and Sven Joeckel. “Video game rating systems in the US and Europe: Comparing their outcomes.” Sage Journals, 17 May 2013, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1748048513482539. Accessed 24 February 2022.

I found this article on Sage Journals under the “International Communication Gazette.” It was published by Leyla Dogruel and Sven Joeckel on May 17, 2013. This article compares the different outcomes that result from video game rating systems in the US and Europe. As I research different solutions for my advocacy project, I noticed a common obstacle that obscures a worldwide solution from being born. Even though video game addiction is a problem felt globally, differing cultures cause each system to have a “distinct focus, according to which it regulates different video game use more strongly than the other systems.” There are different standards for what is acceptable and contrasting regulations that would only work in some countries. The study shown in the article, “applies a comparative perspective on the actual rating practices, asking how far regulation systems differ systematically and how far these differences might lead to different rating decisions.” Proposing a solution will be difficult because considering the circumstances of all countries would be too complex. If a list of options were to be proposed, policymakers and advocates would need to choose methods that work best amongst their people. I think it’s important to remember that there isn’t always a universal solution to solve universal issues.

Global Times. “China to implement nationwide electronic ID authentication for young gamers.” Global Times, 27 September 2021, https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202109/1235257.shtml. Accessed 24 February 2022.

Global Times published this article titled, “China to implement nationwide electronic ID authentication for young gamers,” on September 27, 2021. As I was researching different policies in relation to my advocacy project, I came across this article on top of many others that cover a similar story. I found that China seems to be mandating policies against video game addiction frequently within the past few years and that trend has yet to cease. I found it interesting that these efforts are being made “to prevent gaming addiction and create a better gaming environment for young people,” even though there have been reports of negligence. It made me realize that these policy actions are not necessarily the most effective in combating video game addiction, but it also reflected how different countries are attempting different methods to fit their own standards.

Hsu, Tiffany. “Video Game Addiction Tries to Move From Basement to Doctor's Office (Published 2018).” The New York Times, 17 June 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/17/business/video-game-addiction.html. Accessed 24 February 2022.

This source from the New York Times was written by Tiffany Hsu on June 17, 2018. This article was written around the same time that WHO decidedly diagnosed video game addiction as a “gaming disorder.” Hsu talks about the reality of gaming addiction and how professionals up until this point haven’t been able to properly treat those with it because of how little attention it’s received. I found this article to be helpful because it brought my attention to how little information we have about it. ‘“We don’t know how to treat gaming disorder,” said Nancy Petry, a psychology professor and addiction expert with the University of Connecticut. “It’s such a new condition and phenomenon.”’ This article was written in 2018, yet not much has changed since this claim had been made. This idea that any addiction can be treated the same is flawed and I think my research should include this to spread awareness.

Indeed Editorial Team. “10 Ways To Advocate for Patients.” Indeed, 6 May 2021, https://www.indeed.com/career-advice/career-development/advocating-for-patients. Accessed 24 February 2022.

The Indeed Editorial Team published an article titled “10 Ways to Advocate for Patients,” on May 6, 2021. Though this article did not directly have anything to do with video game addiction, I found it to be useful in my research to find better treatment ideas for gaming addicts. There are many different types of addictions and depending on what it is, treatment plans can differ. This source was helpful in letting me understand what it means to properly treat a patient and care for their well-being. “Patient advocacy is a part of healthcare that concerns sharing, expressing and speaking up for the rights or wants of the patient, group of patients or the caregivers of the patient.” I feel that the personal and private element of patient care is still missing from treatment for those who suffer from gaming disorder. I found this information useful in justifying my argument for more attentive care towards video game addicts.

Kattula, Dheeraj, et al. “A game of policies and contexts: restricting gaming by minors.” The Lancet, 1 December 2021, https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanpsy/article/PIIS2215-0366(21)00427-2/fulltext. Accessed 24 February 2022.

On December 1, 2021, Dheeraj Kattula, Sharad Philip, Avinash Shekhar, and Aniruddha Basu published an article in The Lancet. It recaps another regulation that was “introduced in China restricting the amount of time minors (children and adolescence <18 years) can play video games to 1hr a day on Fridays, Saturdays, Sundays, and public holidays.” They also discuss other policies and actions taken by countries such as South Korea, Singapore, Japan, and India, to update us on the movements against gaming addiction in Asia. In relation to my particular topic of research, the article also mentioned how “many countries have reported an increase in the amount of time younger generations spend playing video games during the stay-at-home directives indicating a probable increase in problematic gaming, especially in minors.” As mentioned in my context project, gaming addiction didn’t just recently become an issue. It has, however, exponentially become a prominent issue due to the covid lockdown initiative.

Király, Orsolya. “Policy responses to problematic video game use: A systematic review of current measures and future possibilities.” NCBI, 2017, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6426392/#B80. Accessed 24 February 2022.

This article was published online on August 31, 2017, in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), by Orsolya Király, Mark D. Griffiths, Daniel L. King, Hae-Kook Lee, Seung-Yup Lee, Fanni Bányai, Ágnes Zsila, Zsofia K. Takacs, and Zsolt Demetrovics. This source, published under the section “Journal of Behavior Addictions,” aims to discuss the functional and psychological impairments video games may have on gamers. “This paper provides a systematic review of current and potential policies addressing problematic gaming.” I found this article to be very helpful in considering options that have already been attempted in the past and the effects it had as a result. This source mainly discussed the difficulties we’d have due to the fact that solutions “largely [depend] on the political system in a given country.” “It is also important to note that general cultural factors and changes need to be taken into consideration when planning policy actions.” These points are useful to me because it ensures that I consider these factors while working on my research. As an advocate, it’s a challenge to not only think of solutions, but to consider all the downfalls you may face. With such a widespread issue being discussed, I would need to consider why previous methods have failed and how they can be improved in the future.

“r/StopGaming icon.” Reddit, https://www.reddit.com/r/StopGaming/. Accessed 24 February 2022.

This link leads to a site called Reddit, where a group of advocates set up a forum titled, StopGaming, in order to help those who need support. Instead of using this site for critical information or evidence, I used it to see what it would be like to browse as a potential addict looking for help. Reddit may not be a reliable source, but this particular platform provides a community through relevant means to those who seek a confidant. I appreciate the casual nature of this particular forum because it may be easier for people to communicate through it and feel the support from others without feeling pressured. One of the members posted an edit that reads, “Fortnite addiction contributed to 5% of all UK divorces this year.” Even if it doesn’t make you quit right away, I think reading through everyone’s personal stories and posts can help you step back from gaming and see it from a new perspective.

Santos, Raisa. “Video Games Help People To Connect And Engage During COVID-19.” Health Policy Watch, 15 July 2021, https://healthpolicy-watch.news/video-games-helps-people-to-connect/. Accessed 24 February 2022.

“Video Games Help People to Connect and Engage During COVID-19” is an article published on Health Policy Watch by Raisa Santos on July 15, 2021. I feel that I used this article effectively in establishing a counterargument for my advocacy evaluation. This particular article portrayed the exact opposite point of view of my own in the sense that Santos sees the positive in gaming. They claim that gaming addiction isn’t real and is instead an overreaction to the increase in recent game activity. Santos argues that “people found solace in video games…to share and keep in touch with peers while playing together,” during the Covid lockdown. I decided to form a rebuttal against this claim by addressing increased game play overall. It is because people found solace in gaming that the number of hours spent playing have increased exponentially. Gaming addiction is still very much real even if people find it positively stimulating.

Snider, Mike. “Video games 2021: COVID-19 pandemic led to more game-playing Americans.” USA Today, 13 July 2021, https://www.usatoday.com/story/tech/gaming/2021/07/13/video-games-2021-covid-19-pandemic/7938713002/. Accessed 24 February 2022.

This news article published by Mike Snider on July 13, 2021, on USA Today, was titled “Two-thirds of Americans, 227 million, play video games. For many games were an escape, stress relief in pandemic.” His article mentions how a survey had revealed that “most players (90%) said they will continue playing” games even after the quarantine restrictions have been lifted. The pandemic increased gaming consumption to the point where there is no going back. The gaming industry had advanced to meet consumer demands during the unprecedented lockdown and had successfully hooked enough players to continue as time goes on. This source was particularly useful in connecting my topic of gaming addiction to the effects of the Covid pandemic.

Kyodo. “Kagawa passes Japan's first ordinance to tackle gaming addiction.” The Japan Times, 18 March 2020, https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2020/03/18/national/kagawa-japan-ordinance-gaming-addiction/. Accessed 24 February 2022.

On March 18, 2020, Kyodo published an article in The Japan Times titled, “Kagawa passes Japan’s first ordinance to tackle gaming addiction.” I came across this article while researching gaming policies around the world. The article revealed that “a local assembly has passed Japan’s first ordinance aimed at reducing internet and video game addiction among young people, by recommending that screen time be limited to one hour per day…despite it having no enforcement mechanism.” Similar to China and Korea’s attempt at controlling video game addiction through mandates and policies, Japan faced little success in forcing limited screen time. It also explains that the problem with these policies was their lack in power to enforce. People, not just in Japan, would find ways to get around these mandates as if the restrictions only fed their motivation and desires. I also found this to be helpful in explaining why you have to tackle the root of the problem first, not just the surface.

TEDx Talks. “Escaping video game addiction: Cam Adair at TEDxBoulder.” YouTube, 17 October 2013, https://youtu.be/EHmC2D0_Hdg. Accessed 24 February 2022.

This multimodal source, which was posted on October 17, 2013, is a Youtube video by TEDx Talks, of the speaker Cam Adair. Adair was an important figure discussed in my context project because he is an advocate for solving video game addiction. He believes that “If you understand why you play games, you can move on from them.” This idea is important because policies up until now have mainly focused on limiting game play instead of treating the root of the problem. “We are so caught up in asking whether this is a real addiction or not that we’ve lost sight of what truly matters: How do we help these people stop playing video games?” It isn’t necessarily about restricting people from playing video games. It is about helping people understand why they rely on games in the first place and helping them find other ways to fill that hole in their life. I feel like mandates, such as the ones implemented by China and South Korea, aren’t effective because it’s as if they’re covering up a giant hole in a wall with a picture frame. It appears like a solution from the outside, but it never fixed the initial problem. I agree with Adair’s mindset here and think that it will help me debate bigger and better solutions.

“Treatment Options for Video Game Addicts.” Video Game Addiction, https://www.video-game-addiction.org/video-game-addiction-treatment.html. Accessed 24 February 2022.

Videogameaddiction.org is an online forum that provides information about gaming disorder including causes, symptoms, help, treatment and more. It’s a lot more information oriented, which is useful for those who may be interested in learning about it, but are hesitant in approaching someone about it. I included this source, since I mentioned it in my essay, but also because it also strongly emphasizes that “video game addiction is real. People of all ages, especially teens and pre-teens, are facing very real, sometimes severe consequences associated with compulsive use of video and computer games.” I found it interesting that they also feature a blog that includes articles that go beyond gaming addiction. All of which cover topics that a gaming addict might be facing, and or might be running away from through the usage of video games.

Woolley, Liz. “On-Line Gamers Anonymous.” Welcome to On-Line Gamers Anonymous®! | On-line Gamers Anonymous®, 2002, https://www.olganon.org/home. Accessed 24 February 2022.

The online forum titled, “On-Line Gamers Anonymous,” was founded by Liz Woolley in 2002, when her son, who was a video game addict, committed suicide. This advocate provides resources and social outlets for addicts to come and seek the help they need. “Participating in OLGA/OLA-Anon is a healing journey for all of us. We respect the need for privacy and ask all who choose to participate agree to this: Who you see here, what you hear here, when you leave here, let it stay here.” My advocacy evaluation includes compassion with those who seek help. I found this source as a great example of advocates offering a safe house for addicts also a community that is experiencing the same issues. This particular forum provides online meetings through Zoom and Google Meet, as well as an online chatroom. Since gaming addiction is somewhat of a technology based issue, I appreciate that their solution is also technology based. I imagine that it would be easier to reach a wider audience this way as well.

icons at the top right corner of the subsection.

icons at the top right corner of the subsection.