This is the second submitted draft of my HCP. Since the topic for my first draft was still too broad, I narrowed it down even more to focus on specifically the Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000 (TVPA 2000).

One of the flaws of this paper is the limited amount of sources I only focused on citing from "Brown" and "Creighton Law Review", which are both color coded in the paper. As you can see, I nearly cited all my sources from those two for my whole paper.

Also, it is apparent that my work cited is very limited as it only contains four sources.

Sex Trafficking and its Laws in the U.S.

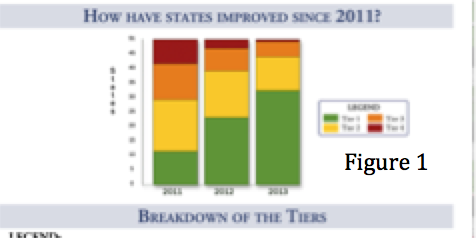

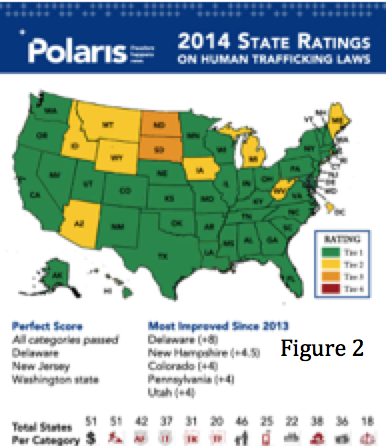

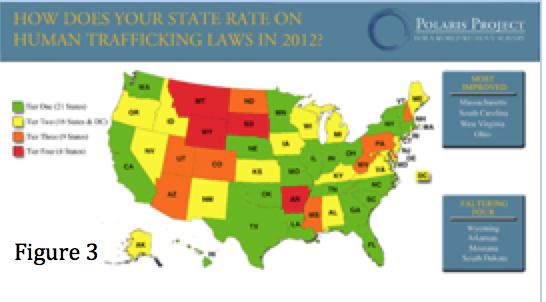

The United States has enforced many anti-human trafficking policies to bring its attention as one of the most prominent issue to resolve. According to the Polaris Project, an organization that works on all forms of human trafficking and serves victims of slavery and human trafficking, 39 states passed new laws to fight human trafficking in the past year and 32 states are now rated in Tier 1 from 21 states in 2012. Figure 3 shows the overall imporvement of state laws aganst human trafficking from 2011 to 2013. Figure 2 and 3 illustrate the transition of how states have improved its laws and awareness and increased its tier score, which measures how critical and effective they combat human trafficking. According to the ILSA Journal of International & Comparative Law, Congress passed the Trafficking Victims Protection Act in 2000 to combat trafficking by recognizing it as a modern form of slavery and also to ensure punishment of traffickers while protecting the trafficked victims. In 2002, President George W. Bush published the National Security Presidential Directive Twenty-Two (NSPD-22) to adopt zero-tolerance policy for the participation in trafficking by any government employee, military or civilian. In 2004, Department of Defense Inspector General stated that one of the main issues for the continued trafficking problem was that leaders had failed to "promulgate and enforce principle-based standards for subordinates who create the demand for prostitution, generally, and for sex slavery specifically." As a result, the Uniformed Code of Military Justice (UCMJ) was amended to criminalize prostitution and enforce punishments consistently. However, within which to prosecute perpetrators and effectively assist victims, enforcement of anti-trafficking laws, these policies and laws are flawed in many perspectives.

According to Creighton Law Review, The Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000 defines sex trafficking as the recruitment, harboring, transportation, provision, or obtaining of a person for the purpose of a commercial sex act. It is consisted of three levels: prevention, protection, and prosecution. The prevention level carries out an annual report assessing the efforts of governments in meeting minimum standards in preventing trafficking. The protection level includes assistance programs providing medical services and hosing to victims. The prosecution level ultimately identifies and prosecutes sex traffickers. Yet, according to Creighton Law Review, nine years after the initiation of the TVPA, only 1,300 trafficking victims had benefitted from the "T-Visa" status compared to the tends of thousands of victims that are still illegally transported into the United states on a yearly basis. It is obvious to one that this policy has not been so effective and the problem lies in the certification process of the “T-Visa” status. In order to assist trafficked victims, the “Victims of Trafficking in Person (T) nonimmigrant visa” is granted and allows victims to be able to remain in the United States if he or she agree to assist the U.S. government in investigating and prosecuting the perpetrators of the crime. In order to qualify for the visa, “(1) according to the laws of the United States, the individual has to be defined as a "victim of sex trafficking;" (2) the individual must be in the United States or any other recognized country as defined by the law; (3) the individual, unless seventeen years old or younger (or physically incapable or if so traumatized psychologically), must agree to cooperate fully with law enforcement in regards to the inquiry and trial of the traffickers; and (4) the individual must be able to demonstrate that he or she would "suffer extreme hardship involving unusual and severe harm" if forced to return to her country of origin” (Creighton Law Review). Impediments arise in this certification process with properly identifying the victims of the sex trafficking industry, figuring out who is a victim of a severe form of sex trafficking, and requiring mandatory assistance in prosecution of sex trafficker.

The U.S. government has shown inadequacy in identifying individuals as sex trafficking victims with their insufficient knowledge and limited perspectives. According to Creighton Law Review, the biggest challenge of identifying victims is the dissident and hidden nature of the trafficking industry as victims are transported into host country illegally with immigration status, which helps the traffickers hide the victim. Traffickers may recruit and promise the victims they will be “singing, dancing and entertaining in other countries” (Brown), pay off their debt and “use the act to coerce her into signing a labor contract” (Brown), and hold false “talent auditions for young women to go and audition to be entertainers for clients, with the promise of better pay in other countries” (Brown). Therefore, many victims do not realize that they are victims and are being exploited and come to rely on the traffickers because of these factors. Also, traffickers use fear to suppress and hide the victims as “where upon arrival they are repeatedly beaten, raped, and starved until they consent to working as the employer desires” (Brown). Some are even “trapped through fear relating to cultural beliefs and superstitions” (Creighton Law Review). What makes victims so difficult to identify is because this “lack of knowledge and understanding exists within the ranks of governmental officials tasked with assisting these victims” (Creighton Law Review) and many have an inaccurate stereotypical image of sex trafficking victims.

Another factor that the U.S. government fails to identify is the victims’ self-identity. According to Creighton Law review, the main reasons why victims contacted by agencies to help them go unassisted is because the victims do not identify themselves as victims and the agencies themselves are unable to identify the victims as victims as well. Many victims do not perceive themselves, as “victims” because they do not know what they have been subjected to is a crime. Also, the traffickers often convince the victims that they are the criminals themselves and are deserving of their situation. Yet, according to Creighton Law Review, many governmental officials see the victims as criminals (prostitutes) and find that the easiest thing to do is have the person arrested and charged with a crime (and where applicable, deported). Ultimately, these acts stigmatize sex work and strengthen the traffickers’ position instead. According to Human Rights for All, laws, policies, and attitudes that criminalize sex workers perpetrate human rights violations and actually work against creating safe and healthy communities. When sex work is illegal, sex workers face societal and legal barriers in accessing safe housing, other forms of employment, birth certificates for their children, and health care services, including HIV/AIDS prevention, treatment, and care. Criminalizing sex work also puts sex workers at an increased risk of violence, be it perpetrated by clients, brothel madams, or even law enforcement officers, and makes it challenging to pursue protection.

One of the biggest flaws of U.S. sex trafficking laws is their failure to recognize the desperate and voluntary nature of sex trafficking victims. According to Creighton Law Review, the certification process dichotomizes between victims that are brought into the sex industry through “force, fraud or coercion” and those who “voluntarily” come into the industry. Yet, they only offer assistance to those who are brought in by “force, fraud or coercion” because it is considered as a sever form of trafficking and those who are not brought into the industry via “force, fraud, or coercion” are not considered to be under a severe form of sex trafficking therefore won’t receive help. According to Vanessa von Struensee, a editor of the Murdoch University Electronic Journal of Law, because these women may have entered the U.S. or other countries illegally and are often working in an illegal industry, they are afraid to turn to local authorities for help and are unable to file civil suits against their abusers or have access to other protections provided by labor laws. In such cases, the criminalization of prostitution where the victim prostitute is prosecuted "adds to the burden of women who are already victims," noted Mary Robinson, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights.

The requirement to assist in prosecution as the part of the certification process is also an impediment of the TVPA as well. According to Creighton Law review, the law specifies that in order to receive the social benefits, a victim must be willing to cooperate with the state in the prosecution of the trafficker. By setting this requirement, the U.S. government fails to realize the brutal treatments that these victims have endured. These “ women (not children as this requirement does not apply to those seventeen and younger) have been traumatized and brutalized to the point of what one author equates to post-traumatic stress disorder” (Creighton Law Review). With these traumas, victims are still expected to “assist, operate and testify in a court of law against the perpetrators that have inflicted this atrocious harm on them” (Creighton Law Review). Also, one of the main problems with this requirement is the unwillingness of the victims to testify for many reasons. According to Creighton Law Review, fear of retaliation of themselves, family and friends is one of the greatest reasons for a victim to not assist in the prosecution. Ironically, the U.S. government has assisted the victims with services by enslaving them to re-victimization all over again.

Another impediment of U.S. government has combating human trafficking is how it ties down sex trafficking only with prostitution. The crime of sex trafficking does not cover sexual violence that is unrelated to commercial sex acts. For example, there are many women, girls, and boys who are kidnapped, raped, and held captive, but unless they are used for a commercial sex act, they are not considered to be victims of sex trafficking, which makes majority of the victims still invisible to our society’s awareness. According to Human Rights for All, from 2000 to 2008, as part of its response to both human trafficking and the global HIV epidemic, the U.S. government developed anti-prostitution policies and Congress passed anti-prostitution provisions that directly undermine U.S. efforts to prevent trafficking and HIV/AIDS as the focus of these policies is directed at stopping women from selling sex to earn a living. Conflating human trafficking with prostitution results in ineffective anti-trafficking efforts and human rights violations because domestic policing efforts focus on shutting down brothels and arresting sex workers, rather than targeting the more elusive traffickers. The problem will therefore never be solved if the U.S. does not target sex trafficking from its roots. According to the first phase of the case, Assessment of Department of Defense Inspector General efforts to Combat Trafficking in Persons, United States Forces Korea (USFK), the Office of Inspector General of the Department of Defense (DoD) initiated a “through, global and extensive” assessment to address publicized allegations that “U.S. military personnel, particularly those stationed South Korea, are engaged in activities that promote and facilitate the trafficking and exploitation of women”. According to Brown, during the assessment, the USFK worked diligently to equate prostitution with trafficking in persons, and has done so by designing the educational programs to correlate prostitution with trafficking in persons. However, the problem arise through the assumption that trafficking in persons is associated with only prostitution, that “essentially these results, at best, only indicate that the participants did not know, or admit that they knew, any soldiers whose off-base activities included the patronization of prostitutes” (Brown). Information about soldier’s participation with the trafficked person working in other roles is totally excluded. The issue reflects the flaw of the DoD and the overall concern the Untied State’s anti-human trafficking policies, that they tend to ignore the fact that the nature of trafficking does not only include prostitution but many other jobs and demands for the trafficked person. Brown therefore offered a perfect example with the role of a “drinky girl” from a bar, that “a woman may never solicit sex from soldiers, but she will solicit twenty dollar drinks in exchange for her companionship. Although there is nothing illegal about soliciting ridiculously expensive juice, the underlying issue is that there is still a function, and thus a demand, for trafficked persons”. The flaw of the NSPD-22 is revealed as it may but not completely subject the soldier’s action into the participation of trafficking, “in the sense that when a soldier buys one of these women a drink, he has validated her reason for being there” (Brown). The nature of sex trafficking is not only prostitution but its association with other activities such as violence, entertainment and involuntary services, as a result, tying sex trafficking down with prostitution will only limit the U.S. government’s scope of investigation and leaving out millions of potential victims and proves.

The U.S. has improvised its laws to combat against human trafficking, yet while proving moderately effective, there are still many flaws that fail to benefit the victims through the process. The effectiveness of these laws will only improve as they expand their knowledge of the identification of victims and the nature of human trafficking itself.

Work Cited

Brown, Christopher M. "Quit Messing Around: Department Of Defense Anti-Prostitution Policies Do Not Eliminate U.S.-Made Trafficking Demand." ILSA Journal Of International & Comparative Law 17.1 (2010): 169-183. Academic Search Complete. Web. 19 Apr. 2015.

George, Shelly. "The Strong Arm Of The Law Is Weak: How The Trafficking Victims Protection Act Fails To Assist Effectively Victims Of The Sex Trade." Creighton Law Review 45.3 (2012): 563-580. Academic Search Complete. Web. 20 Apr. 2015.

"Assessment of DoD Efforts to Combat Trafficking in Persons." Department of Defense Office of the Inspector General, 10 July 2003. Web.

"2014 State Ratings on Human Trafficking Laws." Polaris. 1 Jan. 2014. Web. <http://www.polarisproject.org/what-we-do/policy-advocacy/national-policy/state-ratings-on-human-trafficking-laws>.

Struensee JD, MPH, Vanessa Vo. "Globalized, Wired, Sex Trafficking In Women And Children." E LAW | Murdoch University Electronic Journal of Law 7 (2000). Print.

icons at the top right corner of the subsection.

icons at the top right corner of the subsection.