Flaws of the Human Trafficking Laws

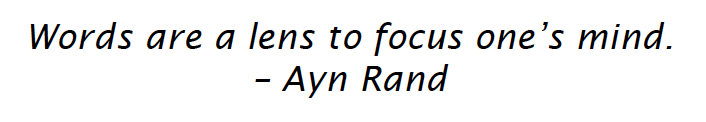

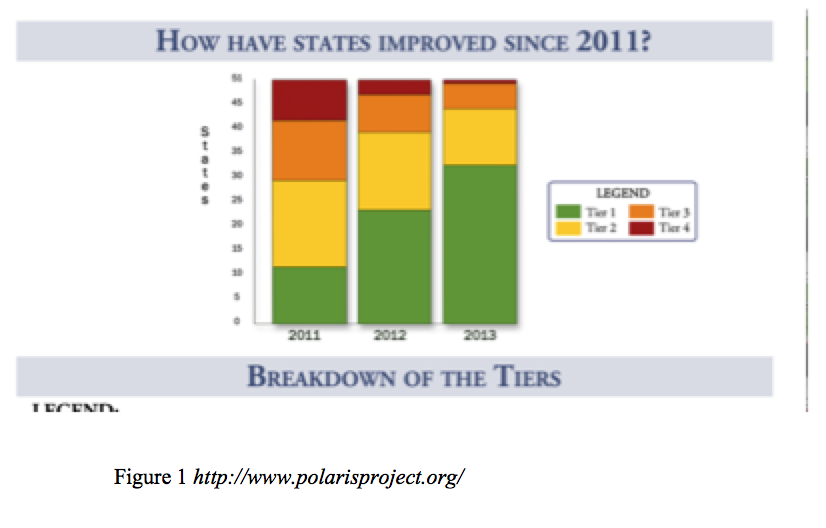

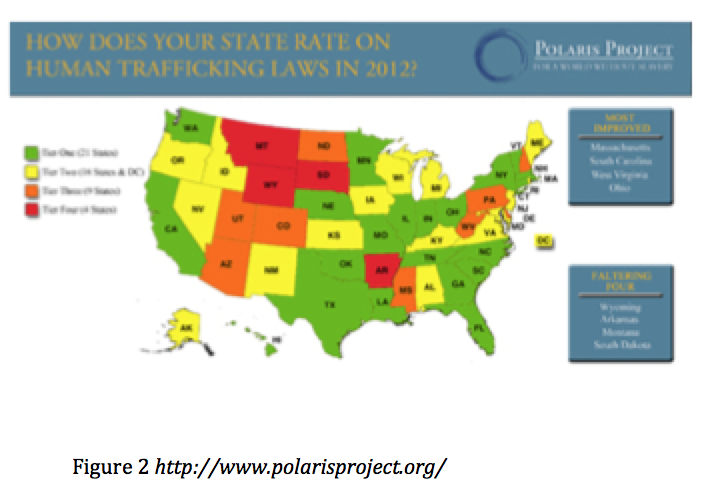

The United States has enforced many anti-human trafficking policies to stop this prominent issue. According to the Polaris Project, an organization that works to combat on all forms of human trafficking and advocates for trafficking victims, 39 states passed new laws to fight human trafficking in the past year. Now, 32 states are rated in Tier 1, which requires the government to fully comply with the TVPA minimum standards, from 21 states in 2012. Figure 1 illustrates the overall improvement of state laws against human trafficking from 2011 to 2013. Figures 2 and 3 illustrate each state and the improvement of their tier scores, which measure how critical and effective they combat human trafficking, from 2012 to 2014. Throughout the years, tremendous improvements and efforts of each state were shown in increasing human-trafficking awareness by actively combating it with amendments of laws and policies. According to the ILSA Journal of International & Comparative Law, Congress passed the Trafficking Victims Protection Act in 2000 to combat trafficking by recognizing it as a modern form of slavery also to ensure punishment of traffickers while protecting the trafficked victims. In 2002, President George W. Bush published the National Security Presidential Directive Twenty-Two (NSPD-22) to adopt a zero-tolerance policy for the participation in trafficking by any government employee, military or civilian. In 2004, the Department of Defense Inspector General stated that one of the main issues for the continued trafficking problem was that leaders had failed to "promulgate and enforce principle-based standards for subordinates who create the demand for prostitution, generally, and for sex slavery specifically." As a result, the Uniformed Code of Military Justice (UCMJ) was amended to criminalize prostitution and enforce punishments consistently. However, even with this large existence and variety of anti-human trafficking laws and policies, human trafficking still exists as a prominent problem of our society today. The problem arises within the flaws of these laws, which can be specifically represented by the Trafficking Victim Protection Act of 2000 including the failure of identifying trafficking victims, understanding hidden nature of human trafficking, requiring mandatory assistance of victims against prosecutors, and limiting human trafficking to prostitution.

Human trafficking has been a serious and ever-present industry that manages to survive even amongst attempts to stop its growth. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Article 3, paragraph (a) of the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons defines human trafficking as the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation. Human trafficking has taken its form as prostitution and slavery for thousands of years and has become one of the most prominent issues in our society today. The United States Congress has declared, “trafficking in persons is a modern form of slavery, and it is the largest manifestation of slavery today” (Harvard Journal of Law & Gender). According to the Protection Project, a not-for-profit human rights research and training institute, human trafficking became a political issue in the early 1900s. In 1902, the International Agreement for the Suppression of the White slave Traffic was drafted with the purpose to “prevent the procuration of women and girls for immoral purposes abroad” (Protection Project). In 1910, the United States passed the Mann Act of 1910, which “forbids transporting a person across state or international lines for prostitution or other immoral purposes (Protection Project). Statistics today shows nothing but how devastating human trafficking has impacted the lives of people especially in the United States. According to End Crowd, a community of modern day abolitionists, there are an estimated 35.8 million people enslaved in the world. Human trafficking creates approximately $150 billion in illegal revenue annually (End Crowd). Modern day slavery can also come in many forms including forced labor, sex trafficking, child trafficking, forced Marriage, bonded Labor and domestic Servitude (End Crowd). According to Allies Against Slavery, an organization that develops community networks that build slave-free cities, 83% of victims in confirmed sex trafficking cases in the U.S. are U.S. citizens, between 100,000 - 300,000 children are at risk to be forced into the commercial sex industry in the U.S. each year, and 86% of U.S. counties with populations over 250,000 that reported sex trafficking was a significant problem. Even with the abundance of anti-human trafficking laws existing today, human trafficking statistics still remain greater than ever before. The issue ironically derives from the laws that enforce human trafficking, that the flaws within these laws have not only failed to protect the victims, but unintentionally helped the traffickers as well. The Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA) of 2000 is the perfect example for the defected nature of these laws and policies.

The Trafficking Victims Protection Act is rated as one of the most important human trafficking law ever passed. According to Creighton Law Review, The Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000 defines sex trafficking as the recruitment, harboring, transportation, provision, or obtaining of a person for the purpose of a commercial sex act. It consists of three levels: prevention, protection, and prosecution. The prevention level carries out an annual report assessing the efforts of governments in meeting minimum standards in preventing trafficking. The protection level includes assistance programs providing medical services and hosing to victims. The prosecution level ultimately identifies and prosecutes sex traffickers. Yet, according to Harvard Journal of Law & Gender, out of the 50,000 women and children that are trafficked into the United States every year for sexual exploitation, only 228 victims received benefits under the TVPA in 2005. Also, according to Creighton Law Review, nine years after the initiation of the TVPA of 2000, compared to the tens of thousands of victims that are still illegally transported into the United states on a yearly basis, only 1,300 trafficking victims had benefitted from the "T-Visa" status, which “allows victims to remain in the United States to assist federal authorities in the investigation and prosecution of human trafficking cases” (U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services). It is obvious to one that this policy has not been so effective and the problem lies in the certification process of the “T-Visa” status. In order to assist trafficked victims, the “Victims of Trafficking in Person (T) nonimmigrant visa” is granted and allows victims to be able to remain in the United States if he or she agrees to assist the U.S. government in investigating and prosecuting the perpetrators of the crime. In order to qualify for the visa, “(1) according to the laws of the United States, the individual has to be defined as a "victim of sex trafficking;" (2) the individual must be in the United States or any other recognized country as defined by the law; (3) the individual, unless seventeen years old or younger (or physically incapable or if so traumatized psychologically), must agree to cooperate fully with law enforcement in regards to the inquiry and trial of the traffickers; and (4) the individual must be able to demonstrate that he or she would "suffer extreme hardship involving unusual and severe harm" if forced to return to her country of origin” (Creighton Law Review). Impediments arise in this certification process of properly identifying the victims of the sex trafficking industry, figuring out who is a victim of a severe form of sex trafficking, and requiring mandatory assistance in prosecution of sex trafficker.

The U.S. government has shown inadequacy in identifying individuals as sex trafficking victims with their insufficient knowledge and limited perspectives of the nature of human trafficking. According to Creighton Law Review, the biggest challenge of identifying victims is the dissident and hidden nature of the trafficking industry as victims are transported into host country illegally with illegal immigration status, which helps the traffickers hide the victim. According to McGeorge Law Review, human trafficking is a hidden crime as they are perpetuated in alleys, brothels and illicit massage parlors. Such discreet locations are perfect for traffickers to hide their victims and use legal false identification such as massagers, waitresses and maids to refer to them. Often, human trafficking victims do not often seek help and may even hide the reality of their situation due to many factors. Traffickers may recruit and promise the victims they will be “singing, dancing and entertaining in other countries” (Brown), pay off their debt and “use the act to coerce her into signing a labor contract” (Brown), and hold false “talent auditions for young women to go and audition to be entertainers for clients, with the promise of better pay in other countries” (Brown). Therefore, many victims do not realize that they are victims and are being exploited and come to rely on the traffickers. According to McGeorge Law Review, the TVPA also ignores how trafficking victims are often highly traumatized, having lived through months or even years of brutality and in some instances develop survival or coping mechanisms that manifest as distrust, deceptiveness and an unwillingness to accept assistance. Also, traffickers use fear to suppress and hide the victims as “where upon arrival they are repeatedly beaten, raped, and starved until they consent to working as the employer desires” (Brown). Some are even “trapped through fear relating to cultural beliefs and superstitions” (Creighton Law Review). Therefore, fear contributes as one of the main difficulties of prosecution as victims are unwillingly to participate as a result. Also, the limited perspectives law-enforcement officers view human trafficking affects the prosecution process as well. According to McGeorge Law Review, human trafficking does not require “physical restraint, physical force, or physical bondage. As a result, a law-enforcement officer under the mistaken assumption that trafficking requires physical restraint will undoubtedly fail to recognize a trafficking victim walking freely about. Ultimately, what makes victims so difficult to identify is because this “lack of knowledge and understanding exists within the ranks of governmental officials tasked with assisting these victims” (Creighton Law Review) and many have an inaccurate stereotypical image of sex trafficking victims.

Another fault is the U.S government's inability to identify the trafficked people as victims, resulting in improper criminalization of these women. According to Creighton Law review, the main reasons why victims contacted by agencies such as Department of Health and Human Services Office of Refugee Resettlement to help them go unassisted is because the victims do not identify themselves as victims.. Many victims do not perceive themselves, as “victims” because they do not know that what they have been subjected to is a crime. These victims are tricked by members of organized crime rings and other traffickers who lure women with the false promises of legitimate jobs that pay decent wages, such as maids, nannies, dancers, and models. As a result, trafficking victims often view their acts as professional careers rather than associated with trafficking crimes. Once these victims become aware of their criminalized situation, the traffickers often convince the victims that they are the criminals themselves and are deserving of their situation. According to McGeorge Law Review, through force and humiliation, traffickers control their victims to convince them that the police will not help them and will be interested only in arresting the victims for crimes committee or for being undocumented. Therefore, a victim may fear deportation if undocumented, have an emotional connection to the trafficker, or fear retaliation from the trafficker. Many governmental officials see the victims as criminals (prostitutes) and find that the easiest thing to do is have the person arrested and charged with a crime (and where applicable, deported) (Creighton Law Review). According to Human Rights criminalizing sex workers perpetrate human rights violations and actually work against creating safe and healthy communities. When sex work is illegal, sex workers face societal and legal barriers in accessing safe housing, other forms of employment, birth certificates for their children, and health care services, including HIV/AIDS prevention, treatment, and care. Criminalizing sex work also puts sex workers at an increased risk of violence, be it perpetrated by clients, brothel madams, pimps, or even law enforcement officers, and makes it challenging to pursue protection. Ultimately, the U.S. government’s failure to identify victims stigmatizes sex work and strengthens the traffickers’ position instead and leads to the dual-victimization of trafficking victims.

One of the biggest flaws of the TVPA of 2000 is its failure to recognize the desperate and voluntary nature of sex trafficking victims. According to Creighton Law Review, the certification process dichotomizes between victims that are brought into the sex industry through “force, fraud or coercion” and those who “voluntarily” come into the industry. Yet, they only offer assistance to those who are brought in by “force, fraud or coercion” because it is considered as a severe form of trafficking and those who are not brought into the industry via “force, fraud, or coercion” are not considered to be under a severe form of sex trafficking therefore won’t receive help. Therefore, a woman who agrees to be smuggled to the United States to work in a brothel in dangerous conditions cannot later claim to be an unwilling victim when arrested for prostitution because she was not “forced or coerced”(Harvard Journal of Law & Gender). Problem arises here, as the law does not recognize the voluntary and desperate nature of human trafficking victims. The victims most in danger of being wrongfully denied certification despite technically qualifying for benefits under the TVPA are victims who have consented to come to the United States and to work in the sex industry, but who find themselves in slave-like conditions—in other words, migrant sex workers (Harvard Journal of Law & Gender). This dichotomy disregards the complexities of sex trafficking and leads to under-certification of trafficking victims as it ignores the voluntary nature of the victims. According to Vanessa von Struensee, a editor of the Murdoch University Electronic Journal of Law, because these women may have entered the U.S. or other countries illegally and are often working in an illegal industry, they are afraid to turn to local authorities for help and are unable to file civil suits against their abusers or have access to other protections provided by labor laws. In such cases, the criminalization of prostitution where the victim prostitute is prosecuted "adds to the burden of women who are already victims," noted Mary Robinson, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights. According to Harvard Journal of Law & Gender, Sex trafficking victims are already at an enormous disadvantage when they encounter law enforcement and other officials. Because they live and work at the margins of society, they are easily and quickly labeled illegal immigrants and prostitutes. Ultimately, the TVPA’s definition of “severe trafficking” understates the nature of human trafficking and therefore poses a major problem to trafficking victims.

The requirement to assist in prosecution as the part of the certification process is also an impediment of the TVPA as well. According to Creighton Law review, the law specifies that in order to receive the social benefits, a victim must be willing to cooperate with the state in the prosecution of the trafficker. If a victim agrees to cooperate, she still can be denied benefits if the prosecutor decides not to pursue the investigation and prosecution (Harvard Journal of Law & Gender). By setting this requirement, the U.S. government fails to realize the brutal treatments that these victims have endured. One non-governmental organization estimated that only half of its clients wished to cooperate in the prosecutions of their perpetrators (Harvard Journal of Law & Gender). There are many factors that lead victims’ unwillingness to cooperate in the “prosecutions of their traffickers, which, on average, last twelve to eighteen months” (Harvard Journal of Law & Gender). These “ women (not children as this requirement does not apply to those seventeen and younger) have been traumatized and brutalized to the point of what one author equates to post-traumatic stress disorder” (Creighton Law Review). With these traumas, victims are still expected to “assist, operate and testify in a court of law against the perpetrators that have inflicted this atrocious harm on them” (Creighton Law Review). Also, one of the main problems with this requirement is the unwillingness of the victims to testify for many reasons. According to Creighton Law Review, fear of retaliation of themselves, family and friends is one of the greatest reasons for a victim to not assist in the prosecution. Ironically, the U.S. government has assisted the victims with services by enslaving them to re-victimization all over again.

Another impediment of U.S. government has combating human trafficking is how it ties down sex trafficking only with prostitution. The crime of sex trafficking does not cover sexual violence that is unrelated to commercial sex acts. For example, there are many women, girls, and boys who are kidnapped, raped, and held captive, but unless they are used for a commercial sex act, they are not considered to be victims of sex trafficking, which makes majority of the victims still invisible to our society’s awareness. According to Human Rights for All, from 2000 to 2008, as part of its response to both human trafficking and the global HIV epidemic, the U.S. government developed anti-prostitution policies that directly focus on stopping women from selling sex to earn a living. Yet, conflating human trafficking with prostitution results in ineffective anti-trafficking efforts and human rights violations because domestic policing efforts focus on shutting down brothels and arresting sex workers, rather than targeting the more elusive traffickers. The problem will therefore never be solved if the U.S. does not target sex trafficking from its roots.

The U.S. has brought its attention to combat against human trafficking as one of the most prominent issues alive, yet, while proving only moderately effective, as there are still many flaws that fail to benefit the victims through the process. The effectiveness of these laws will only improve as they expand their knowledge of the identification of victims and the nature of human trafficking itself through training and modifications of the laws. Unless stricter laws and different perspectives are implemented, victims of sex trafficking will never be saved and will follow the historical trend of being marginalized by the U.S. society.

icons at the top right corner of the subsection.

icons at the top right corner of the subsection.